There is no bicycling in this post. But this journey wouldn’t have happened without an invitation to join a bicycling trip in Europe, so consider it bicycle related.

I was just over a week into my recovery from back surgery last November when I received an email from Mac, a high school friend I’d reconnected with when Rob and I were riding through Michigan in 2019. Would we want to join him and his wife and other friends on a bike and boat tour of Croatia?

Croatia had never been on our radar and we’d never been on an organized bicycle tour, preferring to ride our own pace. But…we really like Mac and his wife Suzie and we’re wanting to explore Europe more, and – most significantly – the trip would begin on my birthday and just over the six-month anniversary from my surgery when all activities would be allowed. The answer was YES.

Somewhere in my emails with Mac I must have mentioned that my grandparents came from Yugoslavia around the time of World War I. I’d never researched exactly where, but Mac told me that their homeland was in Slovenia, only about a hundred miles from where we’d be meeting the boat. With that piece of information I felt obligated to spend a couple days exploring my grandparents’ homeland. I started investigating more. My sister and cousin had information that helped me get started.

The story is one Rob has heard so many times he’s probably sick of it. When asked, “What is your heritage?” My answer is, “All four of my grandparents came from a part of Europe that your’ve never heard of and that no longer exists.” Then I’ll go on to explain that, while my grandparents emigrated to New York City from Yugoslavia around the time of World War I, their homeland was actually a German enclave called Gottschee that was destroyed during World War II.

The Gottscheers were a Germanic people who settled the region in the 1300s but were surrounded by Slovenians. They spoke Gottscheerish, a German dialect which, according to UNESCO, is a “critically endangered language.”

Tensions between the Slavs and Gottscheers ran high prior to WWII and when the Italians occupied Yugoslavia most of the inhabitants were “voluntarily” relocated to a part of Yugoslavia that was closer to Germany. The Italian forces burned down many of the villages to prevent Yugoslavian Partisans from hiding in the buildings.

After the war the Gottscheers were forced to leave their new homes and were unable to return to Gottschee. Many immigrated to the United States where they likely had family in Cleveland or New York. Others settled in Austria.

+ + + + +

On Sunday, April 23, we arrived in Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia, with just enough time to visit the City Museum before it closed for the next few days. I was curious to see if anything about the Gottscheers, or Germans, was included in the history of the city. My research had uncovered the fact that Hitler was responsible for the relocation of Germans from Ljubljana as well as from Gottschee. This wasn’t mentioned in the museum’s historical displays. Rather, one display said that “The end of World War I entailed the departure of the German population from Ljubljana.” I took a photo of another reference to the German people living in the city. I don’t know if these people were Gottscheers or not. There was no mention of Gottschee in any of the history.

After visiting the museum we joined Mac and Suzie and their friend Paul for a boat ride on the River Ljubljanica that ran through the city. Monday, even though it rained throughout the day, we enjoyed a private walking tour, several delicious meals, and a walk up to the Ljubljana Castle.

If you are visiting the Balkans, you won’t want to miss Ljubljana. The old city is closed to cars, straddles the river, and has a large selection of restaurants. Two nights and only one full day wasn’t enough time; hopefully we’ll return.

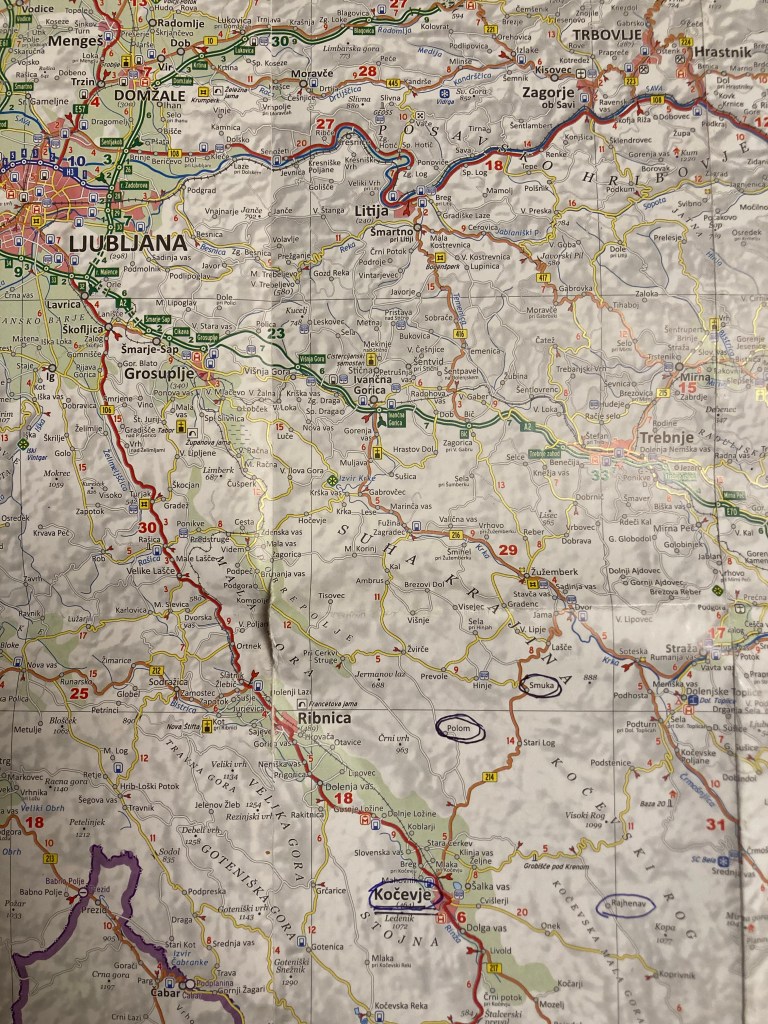

Tuesday morning we picked up a rental car at the airport and drove to Kocevje, the small city that used to be called Gottschee. (While the spelling is very different, the pronunciation is similar – pronounce “Gottschee” and add a “via” at the end” – “Gottscheevia.”) The drive took us through pastoral countryside, away from tourists and big cities. I wondered what it must have been like for my grandparents to leave such a beautiful rural home and land in Queens, New York, with its cement sidewalks, narrow streets, and ever-present traffic.

When we arrived in Kocevje we found our way to the small regional museum that has a permanent exhibit with artifacts and extensive written displays and photographs depicting the history of Gottschee and its people. I took many photos, which you are welcome to peruse here

Kocevje did not strike us as an especially remarkable city. It contains a mix of new and old buildings and, while we obtained a written guide to the historical buildings, we found it to be incredibly difficult to follow the way the map was laid out. But we hit the jackpot with our accommodations. We stayed at the Guesthouse Veronika and found Klemen, the proprietor, to be a wealth of information. He told us that his mother’s family, of Slovenian descent, has been in Kocevje for generations. He is well-versed in Gottschee history. He told us that after WWII the Gottscheers couldn’t come back even if they wanted to. Once the villages were destroyed, the plots for the houses were eradicated so that anyone wanting to return couldn’t even purchase their old land. The Slovenians didn’t want the Germans to come back. I got the impression that, after the death of Tito and the breakup of Yugoslavia, there was more interest in preserving the Gottscheer history.

Below is a photo of the Guesthouse Veronika and Klemen, its innkeeper.

The next morning we embarked on our search of the sites of my grandparents’ former villages. First we set out to find the home of John Koenig, my maternal grandfather. His village, Reichenau (called Rajhenav in Slavenian) was completely destroyed and never rebuilt. Were it not for a tourist farm that has taken over the site, we probably would not have found it.

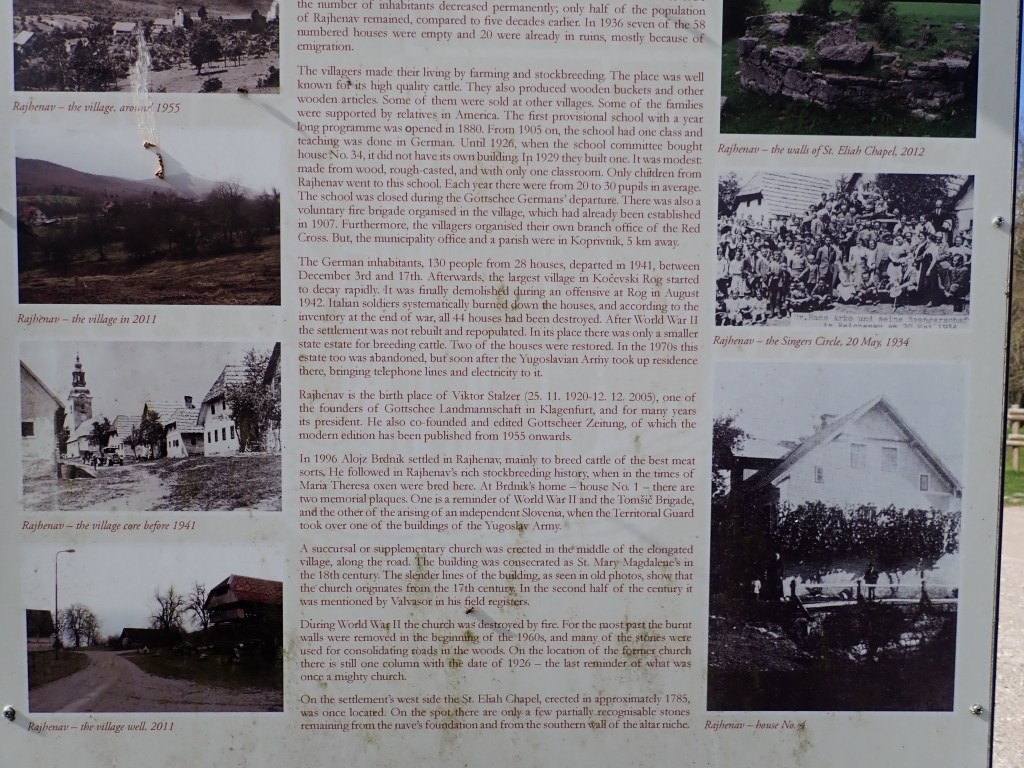

At the end of a dirt road we found the farm, where they raised cattle and donkeys and had rooms for lodging and places to camp. Near where we parked we saw a sign that told the history, in German, Slovenian, and English, of what was once a town.

From the sign we learned that the town had a school, a church, and a fire brigade. The villagers made their living by farming and stockbreeding. Reichenau was well known (and still is) for its high quality cattle. The villagers also produced wooden buckets and other wooden items.

As early as the late 1800s many Gottscheers began emigrating to the United States. In 1869 Reichenau officially had 58 houses and 280 inhabitants. By 1936 seven of the houses were empty and 20 were in ruins. One of those abandoned homes may have been my grandfather’s.

We found a couple women working in the kitchen of the farmhouse. One of them spoke English and offered to show us around. She said she was a friend of the owner and often came to help out for a few days. As we walked around the property, she pointed out the site of the school, the remains of the church, what was left of the foundation of a house, and several old wells.

From what I had been learning about the Gottscheers, many of the men became peddlars, traveling for many months to be able to feed their families. Some villagers relied on family members in the United States to send them money. The soil was poor from cultivating the same crop year after year. The farmers were beginning to try new techniques to get better crops but the Second World War and their forced departure from their homeland left them no opportunity to further their efforts.

I tried to picture what it would be like to live in a town of 58 homes in this beautiful setting. As remote as it felt to drive here by car, it would be that much more remote by horse and wagon. Did my grandfather leave as a young man because he saw no opportunity here, or because he felt hemmed in living in a small community and longed for adventure? Or both? What was it like for him to leave the countryside for a big city?

I believe my grandfather met my grandmother in New York City. Together they owned a bakery in an Italian neighborhood in Queens. They bought several apartment buildings which my mother and aunt eventually inherited and sold. I never met my grandfather. He passed away three years before I was born. He was visiting family in Europe and died while being operated on for a ruptured appendix.

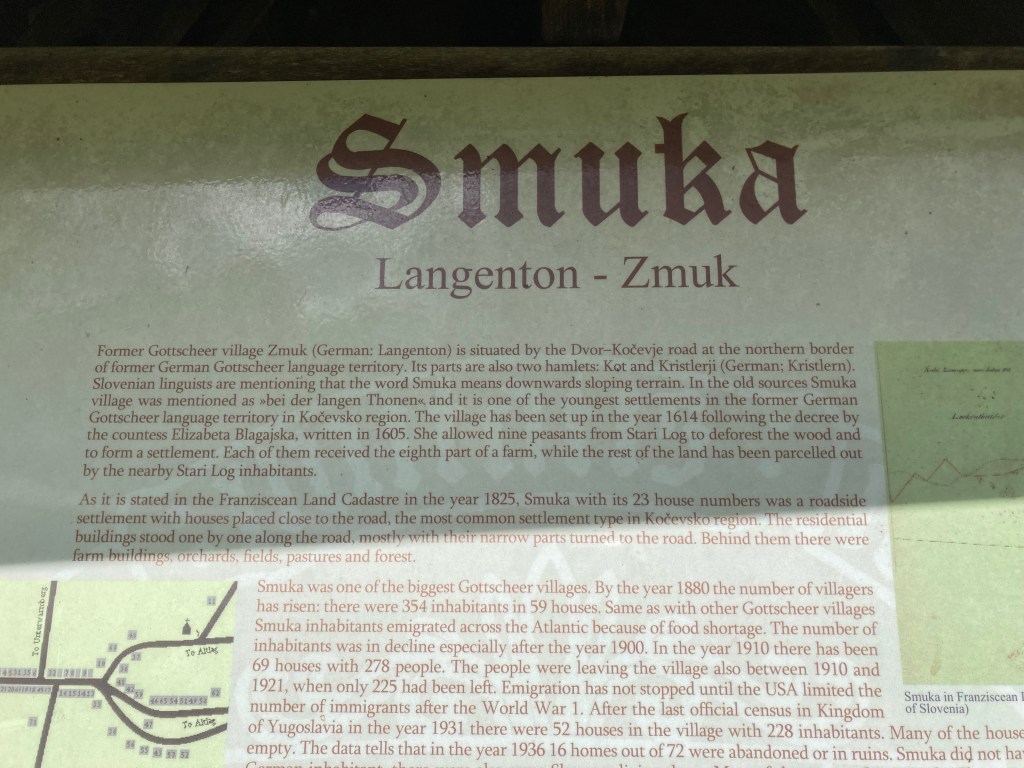

My middle name, Josephine, is for my mother’s mother, Josephine Morscher. She emigrated from the village of Langenton when it was in Yugoslavia. Her father, Franz Morscher, was the mayor, and owned the Franz Morscher Inn.

Langenton (now Smuka) was one of the largest Gottschee villages, a roadside settlement with the houses placed close to the road. Behind them were farm buildings, orchards, fields, pastures, and forests. People earned their living with farming, peddling, and wood trading. But they were poor and by the beginning of WWII many, including my grandmother, had already emigrated to the United States.

Like my grandfather’s town, Langtenton was completely destroyed during WWII.

When we visited the site of what was once the village of Langenton, that had my great-grandfather’s inn, a school, a church, and 72 houses, we found the town of Smuka, just a collection of modern homes built up and down a few roads on the hillside on a quiet country through road. On the edge of town we found a sign like the one in Reichenau describing the history in English, German, and Slovenian. I took many photos of the sign. If you’d like to read more about the town’s history, you can find the photos here.

I couldn’t help but think how fun it would have been if, instead of finding this sterile collection of houses on a country road, we could have pulled into the centuries-old town of Langenton and parked in front of what was once the Franz Morscher Inn, and met people who would be my second and third cousins.

I have been thinking about the similarities between my people and Native Americans. We both lost our homeland. But my grandparents and many of their peers chose to leave and embraced their new lives in the United States. Being Europeans, they easily fit into their new homeland, even while they created vibrant Gottscheer communities in both Cleveeland and New York City. They started businesses and bought real estate. In Queens they started the Gottscheer Relief Society, opened a Gottscheer clubhouse, and held an annual Gottscheer picnic.

My maternal grandmother would come visit us once a week and cook a traditional Gottscheer dinner, food that is similar to German food. She started a project to teach my older sister and me those recipes, but, sadly she passed away just as we’d begun.

My parents, both born in this country, brought their children up with an appreciation of the Gottscheer culture, but that was an aside. We were American.

But what about those Gottscheers who were still living in their homeland when Hitler forced them to leave? Was it a love for the homeland that kept them from following those who emigrated before the war? My mother told me about meeting her aunts and uncles and cousins when she visited Gottschee in 1938 as a young girl. After the war her cousins wound up in displaced persons camps. Did they embrace America the way my grandparents did?

Our last stop was the village of Ebenthal (now Polom) where my father’s parents, Frank Eppich and Theresa Hoegler, grew up. We found it by driving down a quiet country road. Even though it was a through road, it felt incredibly remote. We found no historical sign and no one who spoke English so the only history I can surmise comes from Wikipedia.

Before the Second World War the village had 36 houses and a population of 148. It was not burned during the war, but came under aerial bombardment from Italian, German, and Allied forces. After the war, settlers from various parts of Slovenia moved to the village. Walking around the town I wondered if some of the houses and maybe the church were some of the original buildings.

I never met my paternal grandfather. He died the same week as my other grandfather, hit by a truck when he was standing on a corner in New York City where he had settled. He’d owned a small grocery store and worked in a brewery. My grandmother lived into her nineties. When we would visit her in Queens she was living in a small apartment over a candy store and butcher shop. She owned the building she lived in. She worked well into her seventies in a sweater factory. Like many immigrants she didn’t venture much beyond the community of her family and friends who came from her homeland. Whenever she could she spoke Gottscheerish with others of her generation. She left it to her two sons to integrate into American life.

5 responses to “Finding My Grandparents’ Homeland (that no longer exists)”

Excellent Connie.

LikeLike

Thank you.

LikeLike

Masterfully done Connie. Thank you!

LikeLike

Wow. Such a good story that conjures so many images and questions. We knew you’d love Slovenia! You have such special connection to Slovenia that I didn’t realize. So glad you got to go!

Ljubljana is one of our most favorite cities.

LikeLike

Hi.

I updated my web page,

http://www.morscher.com/

to include your fine tale of your trip to Gottschee. I assumed the trip was made in the year 2023.

Best wishes,

Arnold Hans Morscher.

LikeLike